The imaginary interview with Ettore Toscanini, the founder and inspiration of our company

This is an interview we would have loved to do. Now, we can just imagine. Ettore Toscanini, who would have been 100 years old this year, left us in 2008. If he were still with us, he probably wouldn’t have been a willingly volunteer for a Q&A. It’s not that he didn’t like talking; he was an excellent communicator with an exceptional talent for storytelling. He simply preferred the practical side of things. Celebrating the Company’s 100th anniversary, we interviewed family members, employees, suppliers and friends whose testimonies have helped us imagine a conversation with the man who knew how to give a decisive turnaround to the family’s small business, turning it into an international company.

Family memories, between passions and things done the right way

Q: What are your earliest childhood memories?

ET: There were four of us in the family. Giovanni, my father was born in 1892. My mother, Angela, was five years his younger, and my older brother Ugo, was born in 1920. My family was originally from Bogli, a small village in the township of Ottone, in Val Boreca, above Piacenza. But by 1923, when I was born, they had already been living in the Valsesia for some 20 years. My grandfather Giuseppe, a good “sawyer,” had been called here to work in timber and brought his family with him. It was hard then; there was very little money, and everyone struggled, even the children.

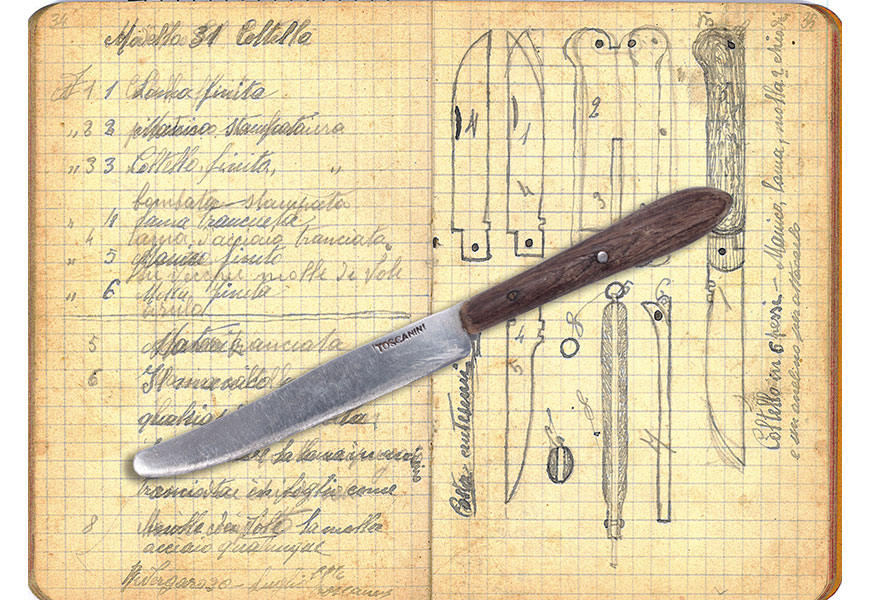

Nonno Giuseppe had started a small sawmill where he made wooden roofing components and sold lumber. My father specialized in making knives with wooden handles. They were beautiful and very durable. Just think! Some of those knives still exist and work perfectly. Father came up with some clever ways to make them stunning and functional. He designed them himself in the notebook he always carried around. He was so good that in ’33, he received his first patent for one of his inventions. It’s all documented, notebook and certificate. We’ve kept it all. My mom used to load knives and other tools into her basket. She visited the markets in the surrounding area to sell them (his eyes glaze over at the memory, editor’s note). She traveled miles and miles carrying a great weight, getting on and off couriers and walking very long distances. I was always moved by her strength and her ability to sacrifice for her family. I still get tears as I travel along those same roads she used to walk down with her load so many years ago. We children had to fend for ourselves while the adults were busy. Actually, we too had to chip in and do our part. I remember my brother and I used to go to the forge near the Besasca creek to beat knife blades for 1 Lira an hour. These small jobs contributed to our family’s livelihood.

Q: Where did your interest in mechanics come from?

ET: My father passed on to me his passion for technical drawings. I have been drawing all my life and have loved being at the drafting table. Trying and trying again, I would find solutions that made it possible to modify machinery. Keep in mind that when we started making hangers, machining tools for this specific product didn’t really exist. You had to be resourceful and adapt to whatever was on hand.

My father also instilled in me a desire to see things done right. Since the best way to get something done is to try, I learned how to design and make tools and machines for exactly what we needed. When I started in the Company, I realized that we would only succeed in moving forward if we could produce more and in less time. Those were years when orders were flying, and everybody wanted to leave behind the hardships of the war. I was in my early twenties then, but I already knew that the success of our small family business depended on the constant improvement of our machining tools. Faster and more precise tools meant more hangers, fewer defects, and fewer returns.

As mentioned, hanger production follows specific steps and ordinary machine tools just couldn’t perform. So I used to modify them and did it so well that manufacturers would often if they could “see” our operations! As a good entrepreneur, I obviously preferred keeping the modified parts to ourselves. We couldn’t lose our competitive advantage.

I’ve always liked mechanics. When you really know their ins and outs, you know the best way to use them. And you can achieve extraordinary results… just like the ones I used to get in endurance racing with my cars, another great passion of mine.

Intuition, a master of life that brings wooden clothes hangers to success

Q: You mentioned hangers, how did this unique expertise come about?

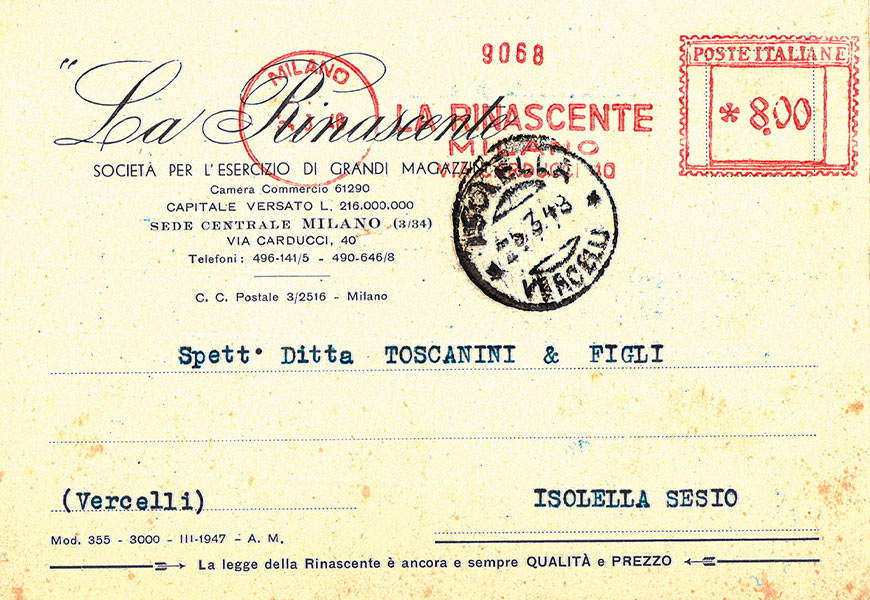

ET: Following the Second World War, when some stability had finally returned, people became wanting more for their homes. Among these desired items were hangers for their clothes. People took great care of what they had in those days; items had to last, be sturdy and ideally well made. I sensed that if we were ready, we’d be able to meet the demand from the houseware wholesalers who were opening their doors again. That’s when the Rinascente, the Milanese department store, came into the picture. I managed to get in touch with its purchasing managers, who were then located in Via Santa Radegonda, next to the Duomo. On 28 February 1948, we became official suppliers.

Communicating in those days wasn’t easy. Just think, we still have a postcard of an invitation for a meeting at that very Rinascente. So if we were to increase our production, it was essential for us to be found! We had one of the very first telephones in all of the Valsesia. The number had only 3 digits, 473! We’ve kept that number, and today it has become 0163 22473.

Factory workers came from the nearby towns. They were hardworking people and even worked on Saturdays when we made the packing crates for our hangers. Cardboard wasn’t available at that time, so we used wood instead. Some of our workers were with us their whole working life, even perhaps joining the Company when just 12 years old. But that’s how things were done then. There wasn’t any school on Thursday mornings, so all the kids would go and do small jobs. Some would come and glue hangers. I remember my father Giovanni used to put apples on the wood stove to bake, and time and time again, the kids would steal them from under his nose. It was a sort of prank. He probably put them there on purpose and just pretended to get upset when they were gone.

My children got to study, but I engaged them in the Company’s day-to-day operations from an early age. I wanted them to learn the ropes and help out when they weren’t busy with school or homework. Giovanni, my eldest son, followed me from an early age, watching and learning how our carpenters and I did things. During the summer, when they had more time, I would give them small jobs like, for example, attaching price tags, assembling boxes or printing customers’ addresses. Cristina inherited my creative vein but also precision, two things that coupled together form authentic talent. Today, she uses her gifts in her own fashion business and does very well. Federica, my third child, would often come with me to our clients where she listened and learned. The sensitivity you need to do things well doesn’t come from books but rather in the field. You learn by asking questions and by trial and error with tenacity and humility.

Q: Speaking of tenacity, they say you were a bit stubborn with quite the personality….

ET: I never asked anyone to do something I wasn’t prepared to do myself. However, if we’re talking about the fact that I am a perfectionist and that I know exactly how I want things done, well, then yes. I don’t accept work done carelessly. Maybe it was because of my upbringing. But more likely, it comes from a sense of responsibility. I’ve always been against any kind of waste. Whether working carelessly, wasting material or person hours, these are all forms of disrespect for oneself and others. I’ve taught numerous people how to work. And if I was harsh, well, I probably was. I’ve trained and shared with more than one generation of exceptionally talented carpenters and laborers.

Q: When was the turning point? When did Toscanini became a brand, like we say today?

ET: If by brand, you mean a company making high-quality, reliable, and ever-changing products, then I would say the late 1980s when we started working with fashion houses. However, we had already been crossing the Atlantic to sell our hangers in some of the most influential American department stores for a while.

Our first couturier was Valentino. We designed a hanger for him called Valentino. From there on, we’ve never stopped and have earned a reputation as a professional and capable partner. The fashion world is demanding. It doesn’t wait and always expects something extraordinary, unique, and at times impossible. But I never backed down or said, ‘this can’t be done.’

Through trial and error and new attempts, I always succeeded. My knowledge of the raw material – wood – and its processing, mechanics and creativity have helped. And yes, you need to be able to envision solutions that aren’t obvious when facing any hurdles. You have to invent different ways, perhaps taken from other industries, to successfully give the customer what they want even when others have said no.

I don’t know if this is what makes a ‘brand.’ My generation didn’t do marketing, but I do know that instinct is something that comes very close. I’ve always used my gut, even when people called me crazy. For example, in the 1970s, when it looked like plastic would undermine wood forever, I converted some of the machines back to making clogs. Rosella, my wife, helped me immensely. And together, we made collections that sold like hotcakes. We ended up selling over 500,000 pairs in one year… and they told me it was crazy.

Beyond clothes hangers: the satisfaction of that extra plûch

Q: There is something else you love besides woodworking and cars, isn’t there?

ET: Ah… yes. Hydroelectric power plants (here his eyes shine, editor’s note). I was born along a river and have always been fascinated by the energy its course generates and the possibility of harnessing it. Here in the Valsesia, there were many power plants, wool mills and spinning mills that used this energy to power their machinery. But in the 1960s and 1970s, a series of disastrous floods and the high cost of running power plants as opposed to oil pushed companies to abandon them… a waste, a real shame. So, I began by salvaging one plant that was in terrible shape. With a lot of hard work and effort, I got it up and running again. Other plants followed along. My son Giovanni has been pursuing successfully this same course, and with as much passion, I would say.

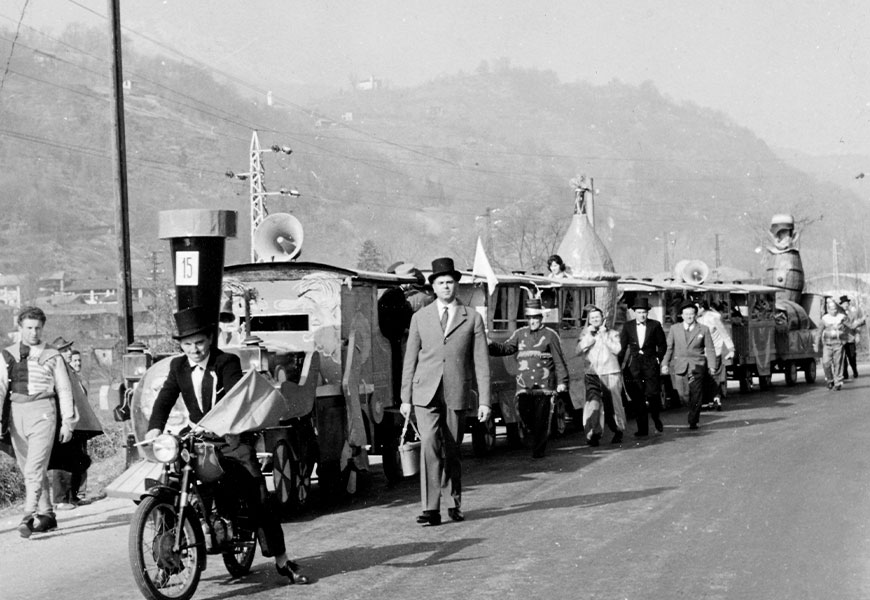

Q: And if I were to ask you about Carnival…?

ET: Ahhh… Carnival in the Valsesia is serious business! Just think, a tradition that is 170 years old this year and is deeply loved by all the people in the Valley. It’s a time of immense human, cultural and artistic sharing. Together with Ugo Pizzi, Gianfranco Zanni, Mario Casagrande, and several other entrepreneurs and merchants in the Valsesia, we revived the tradition that had somewhat died out in the early 1960s. We did it because of our genuine enthusiasm, of course, but also as a social commitment. We invested money, time and resources. I, for example, among other things, was in charge of the little train that carried children around during Carnival festivities. With the help of my artisans, I built a small colorful train complete with train carriages. I am sure our little train is in the photo albums of many former children! Carnival used to be a lighthearted and democratic occasion. Everyone in the town square eating the traditional ‘busecca’ or tripe. We were all equals and I believe it is still the same today. It’s nice to know this age-old tradition hasn’t become just folklore but rather a treasured tradition everyone gets to enjoy.

D: For the Company’s 100th anniversary, a book was put together. It details the Toscanini Company story and its key players. The team that worked on this project had an incredible abundance of material, official documents, notes, images, artifacts, and all sorts of rare-to-find testimonials. But there were very few pictures of yourself. Why is that?

ET: (laughs) I liked taking pictures more than having them taken! A good part of the photographs used for the book, I shot with my Rolleyflex. It was so easy to use and I loved the camera’s versatility.

D: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

ET: I’ve already said far too much for my liking. But there’s one more thing… I worked hard, but I was rewarded with tremendous success. And I am eternally grateful. Knowing that my family has carried on my work makes me proud. Equally important is knowing that I have managed to pass on to my children and the people who work with them the pleasure of doing things well, of always looking for that “plûch,” that extra little something that makes the difference from a well-executed product to one made from the heart as well as from one’s head. And lastly, I’d like to mention my deep bond and sense of gratitude I feel for the Valsesia, my home, my primary source of inspiration. A pride that has made me say proudly on the phone, “This is Toscanini from Isolella.”